Stronger at the Broken Places: The Paradoxical Impact of Failure

Introduction

In adversity, the human spirit has an astonishing capacity to rebound, learn, and grow.

In this article, Dr. Martha Stark, a renowned figure in integrative psychiatry and innovative psychoanalysis, explores the concept of resilience.

She argues that failure can catalyze growth and healing and that we can become more assertive in our broken places. Throughout this article, she ventures into the beauty of brokenness and the quiet triumphs of overcoming hardships.

Expert Opinion

Probably familiar to most of us is Ernest Hemingway’s “The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places” (1957). Many writers since have reiterated this same sentiment, including, more recently, Kelly Clarkson in her well-known song, “What Doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” (2011).

Similarly, an old Japanese adage goes, “Fall down seven times, get up eight.” I love this but, quite frankly, it does not do full justice to the concept of resilience. If a failure is appropriately grieved and responsibility taken for the contribution we might have made to the failure, we will probably end up ahead of the game – wiser for the experience and, indeed, better off for having failed.

So perhaps more to the point would be “Fall down seven times, but stand up ever taller every time thereafter.”

By the same token, people like to say, as if by way of reassurance, that “everything happens for a reason.” I do not specifically subscribe to this, but I do believe that when bad things happen, which is almost inevitable, we will be able to end up ahead of things (indeed, stronger for having failed) if we can commit to learning from the experience and, going forward, perhaps can embrace something new, different, and better than what we might otherwise have invited into our life.

Another benefit from failure is now occurring to me. Once we have fallen and found that we are indeed able to recover, then perhaps, from that point onwards, we will not have to be quite as fearful of falling again because we will know that we have it in us to recover from whatever fall we might have taken.

Parenthetically, I have noticed that Olympic figure skaters will sometimes, almost as if on purpose, fall on an easy step near the beginning of their program – perhaps to get failure and subsequent recovery out of the way – and then go on to skate a clean program!

On another note: Something that I have found helpful as a way of conceptualizing the paradoxical impact of failures, especially over time, is the sandpile model of chaos theory (developed by Bak, Tang, and Wiesenfeld in 1987).

Amazingly enough, the grains of sand being steadily added to a gradually evolving sandpile are the occasion for both its disruption and its repair. Not only do the grains of sand being added precipitate partial collapses of the sandpile (described as minor avalanches by chaos theorists), but they also become how the sandpile will then be able to build itself back up – every time at a new level of homeostatic balance.

The sandpile will therefore have been able not only to manage the impact of the challenge but also to benefit from that challenge. In other words, the evolution of the sandpile will have advanced not just in spite of but by way of the periodic disruptions to its integrity.

What a lovely metaphor for our evolution over time by our ability to manage our failures. Indeed, do we not progress from less evolved to more evolved by way of negotiating and ultimately surviving our various failures? And are not the irregularities in the sandpile, much like the scars we all bear, poignant reminders of the minor collapses (and failures) we have sustained over time but ultimately triumphantly overcome?

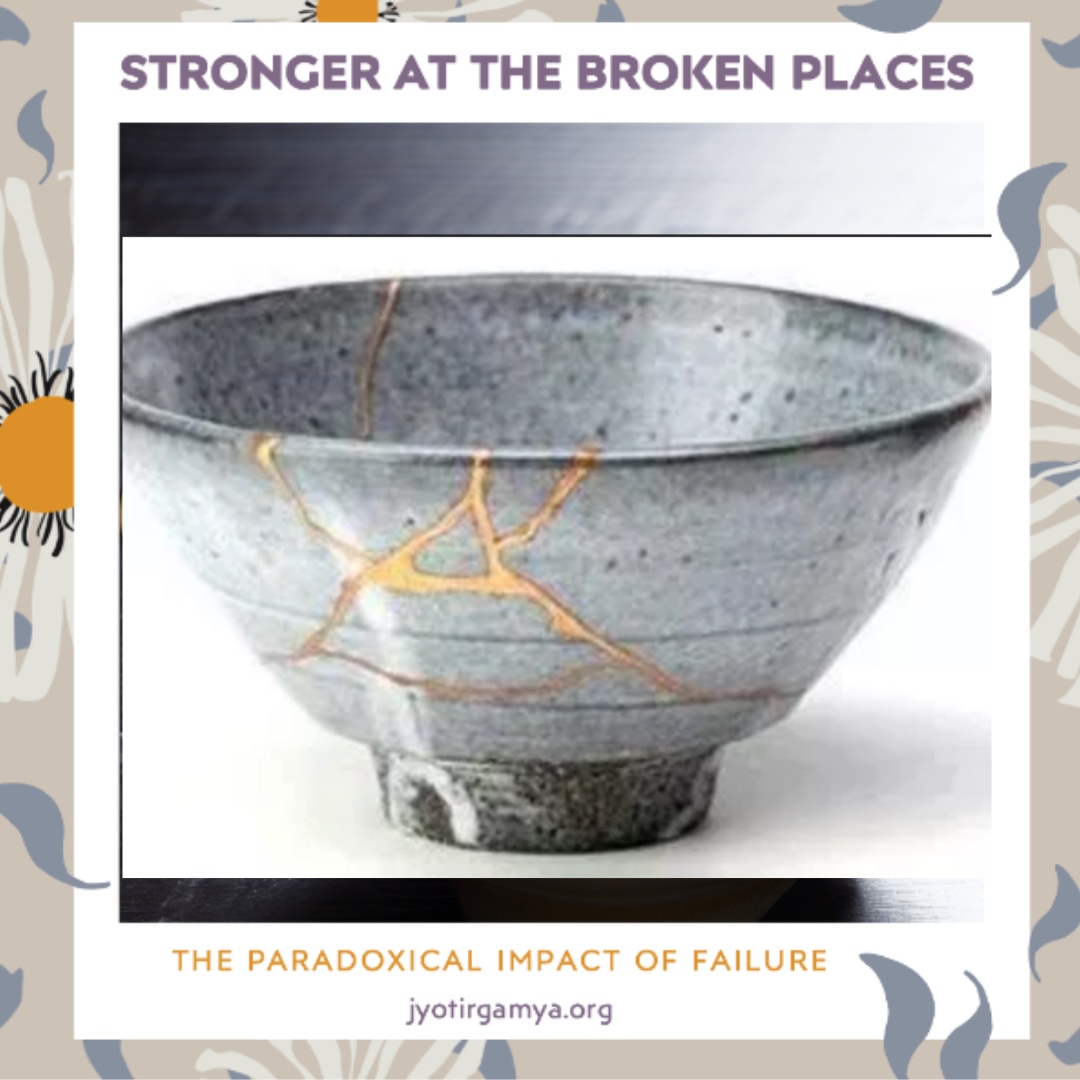

I am here reminded of Kintsukuroi, the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery with gold or silver lacquer and appreciating that the piece will be more beautiful for having been broken.

So I will close with the following as a tribute to the therapeutic impact of failure: If a bone is fractured and then heals, the area of the break will be stronger than the surrounding bone and will not again easily break. I therefore wonder – Are we, too, not stronger at our broken places? And is there, not a certain beauty in brokenness, a beauty never achieved by things unbroken? Do we not acquire a quiet strength from surviving adversity and hardship and mastering the experience of disappointment and heartbreak? And, when we finally rise above it, do we not rise up in quiet triumph, even if only we notice?

References

Bak, P., Tang, C., & Wiesenfeld, K. “Self-organized criticality: An explanation of 1/f noise.” Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 381 – Published 27 July 1987. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.59.381.

Clarkson, K. “Stronger (What Doesn’t Kill You).” Stronger. RCA Records. 2011.

Hemingway, E. (1957). A farewell to arms. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Conclusion

Dr. Stark’s insights have demonstrated that failure can catalyze growth and healing. We can emerge from adversity with greater strength and resilience, just as a healed bone. By learning from our experiences, taking responsibility for our contributions, and embracing new possibilities, we can harness the transformative power of resilience.

Now is the time to recognize the potential within our brokenness, find the beauty in our scars, and appreciate the quiet strength that emerges from surviving life’s challenges. Let us commit to learning from our failures, and as we rise above them, may we discover the extraordinary resilience within each of us.

About the Author

Harnessing Resilience and Relentless Hope for Deep Healing

Dr. Martha Stark, an esteemed faculty member at Harvard Medical School, is a renowned figure in integrative psychiatry and innovative psychoanalysis. With a career spanning over four decades, she has dedicated herself to unraveling the complexities of the human mind and harnessing the potential for growth and healing.

She is the author of nine books on these topics, including The Psychodynamic Synergy Paradigm: A C.A.R.E. Approach to Deep Healing, which has been praised by colleagues and clients alike for its depth, clarity, and relevance.

Dr. Stark’s groundbreaking work revolves around “optimal stress” as a therapeutic tool for provoking recovery. By strategically challenging and supporting her clients, she empowers them to confront and master adversity, resulting in profound healing.

Her exploration of “relentless hope” has been transformative for clients dealing with grief and loss. By guiding them to confront and grieve their pain, she helps them evolve to a place of mature acceptance.

In addition to her faculty role at Harvard Medical School, Dr. Stark is the CEO and faculty member at SynergyMed for MindBodyHealth, a pioneering organization offering state-of-the-art educational programs on integrative medicine.

Dr. Martha Stark’s exceptional expertise extends to her clinical consultation work, especially with “resistant” clients, including those with narcissistic, sadomasochistic, and borderline personality disorders. She believes psychotherapy is a journey of processing unmastered experiences and healing early heartbreak.

With an impressive academic journey, including co-founding the Center for Psychoanalytic Studies at William James College, Dr. Stark remains committed to sharing her knowledge and empowering others to achieve holistic well-being.

Related Articles :

If you think someone would benefit from the article, please do share it with them.

Want to stay connected? Here’s our twitter.