How to Know When Your Work is Finished: Stop Overthinking and Ship With Confidence

You just finished something. The report is written. The design is complete. The code compiles. For exactly three seconds, you feel relief.

Then the doubt floods in.

Should you send it now or review it one more time? This is the moment when perfectionism strikes hardest. Two voices start competing in your head, and whichever one wins will determine whether your work succeeds or fails.

The Two Voices Preventing You From Finishing

The first voice says ship it immediately. It’s good enough. If you wait, you’ll lose momentum. Just get it out there before you overthink it.

The second voice says not yet. One more pass. Polish that section. Fix that transition. Check everything again.

Both sound reasonable. Both come from the same place: fear of putting your work into the world. And both lead to the same outcome - work that doesn’t represent your actual capabilities.

This is actually a game theory problem. You’re playing against your future self, and like the Prisoner’s Dilemma, both obvious moves lead to suboptimal outcomes.

If you ship now and the work has issues, you’ve launched buggy code that creates technical debt. If you ship now and it’s actually fine, you got it out there but wasted the opportunity to catch real problems. If you keep refining and find bugs, great - but you lost time you could’ve spent on other work. If you keep refining work that’s already good, you’ve perfected it but slowed yourself down.

Without information about which outcome you’re facing, both pure strategies are losing moves. The Nash equilibrium isn’t at either extreme.

Not sure which pattern you fall into? Take the Finisher’s Dilemma Assessment to identify your finishing tendencies.

Why Rushing Your Work Always Backfires

When you finish something and immediately send it out, you’re still inside your own head. You know what you meant to say, so that’s what you see. Your brain fills in gaps that aren’t there and smooths over rough edges that would be obvious to anyone else.

This is why you spot typos five seconds after hitting send. Why your “final draft” has formatting errors on the first page. You weren’t being careless. Your brain simply couldn’t see what was actually there instead of what you intended.

Sarah spent three days crafting a proposal for a dream client. Exhausted and eager to move on, she sent it the moment she finished. The next morning she spotted three typos and a budget calculation error. The client noticed too. She didn’t get the contract.

The cost of rushing compounds over time. Each rushed piece damages your reputation slightly. People start expecting errors from you. You spend more time on damage control than you would have spent reviewing properly. You miss opportunities because decision-makers remember the sloppiness more than the quality of your thinking.

How Perfectionism Kills Good Work (The Endless Editing Trap)

The opposite approach seems safer but it’s equally destructive. When you can’t stop editing your work, something insidious happens. You stop improving and start just changing.

Every piece of work has an optimal completion point where it’s clear, effective, and ready. Push past that point and you begin second-guessing instincts that were correct. You edit the personality out of your writing. You overcomplicate designs that were elegantly simple. You add features that confuse rather than enhance.

Marcus built a side project he’d been excited about for months. When it came time to launch, he spent six additional weeks “just polishing” features that were already functional. By the time he finally launched, a competitor had released something similar. His window closed.

Research shows that people forced to stop editing after a set time produce work rated higher by independent judges than those allowed unlimited revision time. The unlimited group edits past improvement and into overthinking.

Signs you’re overthinking your work instead of improving it: you’re tweaking variable names, adjusting margins, rewriting sentences that were already clear. Each change feels productive but you’re not making the work better. You’re making it different.

This is perfectionism preventing you from finishing, and it’s more destructive than rushing because it feels responsible.

The Deliberate Pause Method: Your Solution for Knowing When Work is Done

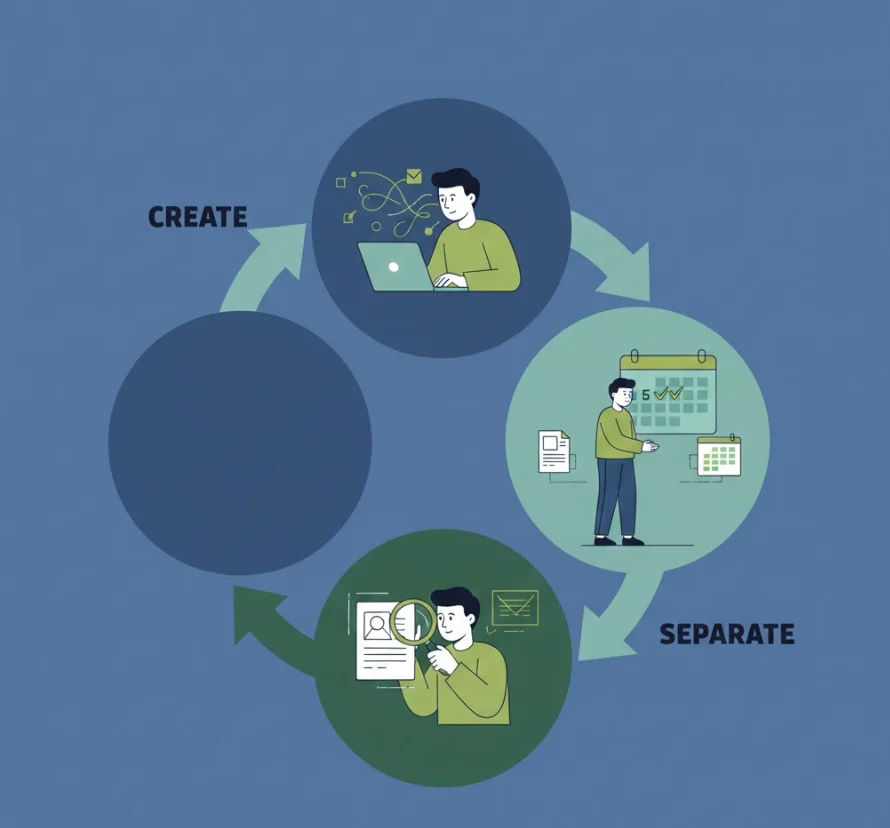

There’s a third approach that avoids both traps, but it requires doing something counterintuitive. When you finish a draft, close it immediately and schedule a specific time to review it later. Not “sometime later” but a specific appointment on your calendar, five to seven days in the future.

Then actually step away. Work on something completely different. Let your brain fully disengage from what you just finished.

This gap creates something neither rushing nor endless polishing can provide. When you come back after several days, you can see the work the way other people will see it. The emotional attachment fades. The memory of what you intended becomes fuzzy. You start reading what’s actually on the page.

This isn’t just taking a break. This is the most important part of finishing. The deliberate pause technique transforms how you evaluate your own work.

Why the 5-Day Rule Works: The Science of Emotional Distance

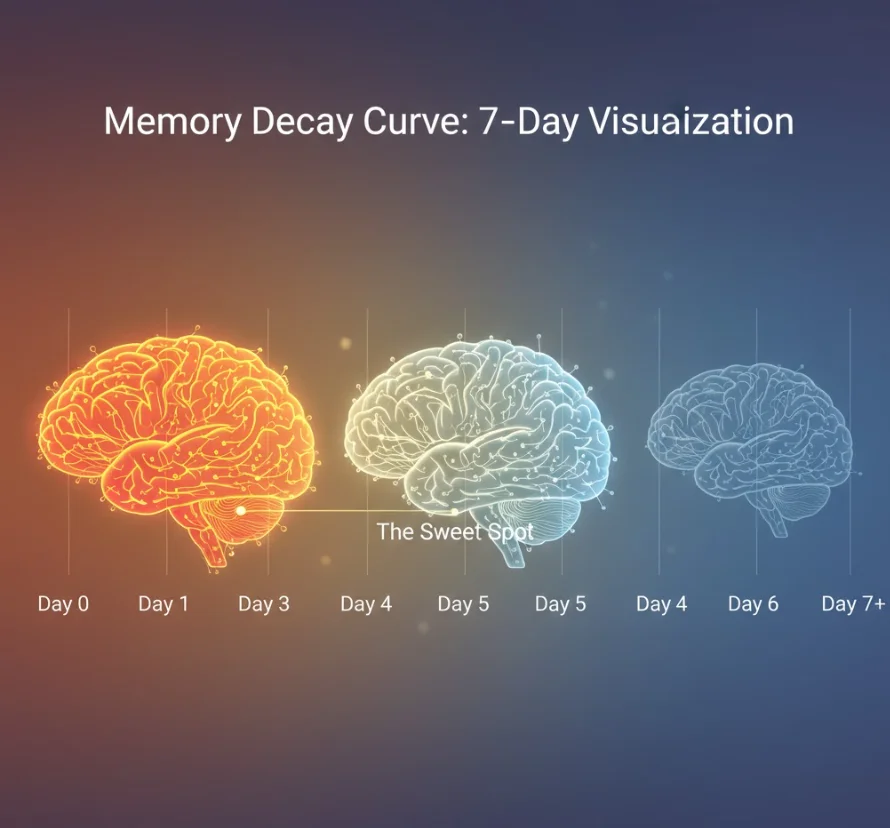

The timing isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on how memory and emotional attachment actually work.

For the first few days after you write something, you remember what you were thinking when you wrote it. You remember the conversation that sparked the idea. You remember what you were trying to emphasize. All that context colors how you read your own work.

Around day five, that detailed memory starts to fade. You still remember the general context, which helps, but you’ve forgotten the specific intentions behind each sentence. This is the sweet spot. You can evaluate the work on its merits while still understanding what it’s trying to accomplish.

Wait too long and you lose important context. Come back too soon and you’re still too close to see clearly. Five to seven days is where most people hit the right balance for overcoming perfectionism in creative work.

How to Stop Editing and Actually Finish: The Objective Review Standard

When you return to your work after the deliberate pause, you need a clear test for what to fix and what to leave alone. The standard is simple but difficult to apply honestly.

Only fix things you would flag if someone else had written this.

If you’re reading a colleague’s report and spot a typo, you fix it. If their logic has a gap, you point it out. If a section is genuinely confusing, you suggest clarification. Those are real problems.

But if you would have phrased something differently, that’s personal preference. If you think a different structure might be slightly better, that’s speculation. If you’re changing word choices that are equally good, that’s fiddling.

The moment you catch yourself making changes without being able to explain why they’re objectively better, you’re done. Close the document and ship it.

Signs You’re Overthinking (Not Improving) Your Work

Your work is finished when you’re changing things rather than improving them. That’s not a subjective feeling. It’s a measurable threshold with clear warning signs.

You’re changing things back to previous versions. You’re editing the same sentence for the third time. You’re adjusting commas and minor word order. You’re switching fonts instead of fixing content. You can’t articulate why a change makes the work better.

These are signals that your objective brain has done its job. Everything after this point is just anxiety pretending to be diligence. This is how you know when to stop revising and publish.

Step-by-Step: How to Implement the Deliberate Pause

You finish a proposal on Monday afternoon. The temptation is strong to review it immediately and send it out. You’re energized. You want to capitalize on that momentum.

Instead, you close the document without rereading it. You open your calendar and create an appointment for the following Monday morning titled “Review Proposal.” You include the file location in the notes. Then you start working on something else.

When You Don’t Have 5-7 Days Before Your Deadline

Sometimes you genuinely don’t have a week. The deadline is tomorrow. The meeting is this afternoon. The email needs to go out in an hour.

The principle still applies, just compressed. If you have an hour before sending an email, write it in the first thirty minutes, then work on something else for twenty before reviewing. If you have a day, finish in the morning and review in the afternoon after different tasks.

The longer the gap, the better the perspective. But even a short gap beats no gap at all.

The other option is to plan better. If something is due Friday, aim to finish by the previous Friday. Build the review time into your timeline from the start. The pause isn’t optional time tacked on at the end. It’s part of the work.

This is how you finish projects without burnout. You’re not constantly rushing or endlessly polishing. You’re working with a system that tells you exactly when good enough is actually perfect.

Stop Overthinking and Start Shipping With Confidence

You now have a complete system for knowing when your work is finished. No more guessing. No more endless revision cycles. No more rushed submissions you regret five minutes later.

The deliberate pause method gives you what perfectionism promises but never delivers: the confidence that your work is actually ready.

Finish your draft. Close it. Schedule your review. Work on something else. Come back with fresh eyes. Fix what’s actually broken. Ship when you start fiddling.

Close your current project right now. Schedule your review for five days from now. Work on something different. When you return, you’ll see your work clearly for the first time.

That’s when you’ll know it’s done. That’s when you ship it.

Related Reading

Beyond Atomic Habits: The Real Reason You Procrastinate

Embrace Imperfection for Better Mental Well-Being

Perfectionism and Servant Leadership: Finding Balance

Ready to identify your finishing patterns? Take the Finisher’s Dilemma Assessment to discover whether you tend toward rushing, endless editing, or balanced completion. Then try the deliberate pause on your next project and track what you discover during the objective review phase.